One of the young boys in my family is currently all about dinosaurs (and monster trucks, living up to all little boy traditions). He is knowledgable enough about them to name the lovely specimen with the incredibly long neck an Apatosaurus, not Brontosaurus, putting his knowledge a caliber above mine at that age. But he may yet be indoctrinated with another of the great dinosaur myths, that each stegosaurus has a second brain in its tail, because even “scientific” documentaries featuring respected researchers get twisted to perpetuate that idea.

Perhaps those dinosaur documentary makers are just jealous that the humble octopus turns out to be so much cooler than their great lizards.

Your average octopus might not seem like a cognitive juggernaut, especially not in an ocean that also contains dolphins, our favorite frontrunner for animal intelligence. Octopuses are invertebrates – the name for animals that lack any kind of spinal column to dangle beneath their brains – a category once thought to be far lower on the evolutionary ladder. We’ve only recently discovered how creative invertebrates get to be with their neurobiology.

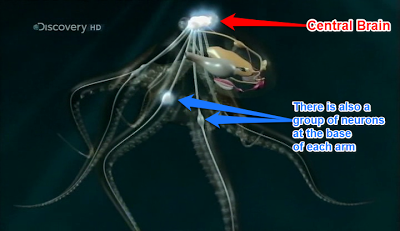

You could say that octopuses have not one brain, but nine: one behind their eyes, and one at the base of each arm – where it connects to their body.

Really though, it’s all one “brain”. Even the human brain is composed of different clusters of neurons that perform different jobs – we give many of them special names like “hippocampus” or “amygdala” – but ours happen to be crammed together in a skull, not unlike sardines in a can. The octopus has simply let some of its sub-regions of the brain drift further away, closer to where they are needed.

Why distribute the octopus brain this way? Probably to get the brain cells where they’re needed most. Even at the incredibly speed of synaptic transmission, distance matters when sending important signals for processing. This is why reflexes are routed through our spinal cords; it’s best if the message that you stepped on a tack only has to get from the foot to your very first vertebrae and back, instead of all the way up to your skull and back. This is what early paleontologists had in mind when they proposed the second stegosaurus brain as well: a special nerve center to control that massive spiked tail. Small “brains” at the base of each arm can process signals from the arms more efficiently…and independently.

This is where octopus brains get just a little disconcerting. The mini-brain controlling each arm contains enough neurons to act more or less on its own, when it wants to. You just can’t argue with evidence that severed octopus arms still react to external stimulation; you can only wonder what else they might do, and hope whatever mind might be behind the arm’s actions is thinking benign thoughts.

And don’t think I’m jumping the gun proposing that there might be some intelligence behind all these distributed neuron clusters. No, I’m not convinced that Paul the octopus could really predict the winners of the World Cup (although he had certainly learned the importance of the German flag). But those mini-brains of the arms working in concert allow octopuses to retrieve food from some surprising locations:

I’m not aware of any other animal, vertebrate or invertebrate, that has shown such facility with opening jars. I know some humans – myself included – who can’t do as well. And octopuses have been documented using tools, in the forms of coconut shells carried around for future use as sleeping bags:

If we go just by number of neurons, then octopuses should not be able to accomplish these feats. It may just be that by spreading their neurons around, instead of corralling them all in one place, they’ve achieved something like a distributed computing network, which can solve problems that one computer alone couldn’t hope to tackle.

So the Stegosaurus may be the winner in capturing young boys’ imagination, with their massive size, armor and spikes. But the octopus has the cooler brain by far. Perhaps that’s why we get to watch octopuses play in museums, while dinosaur skeletons just strike a pose.